Max Formant Analyzer

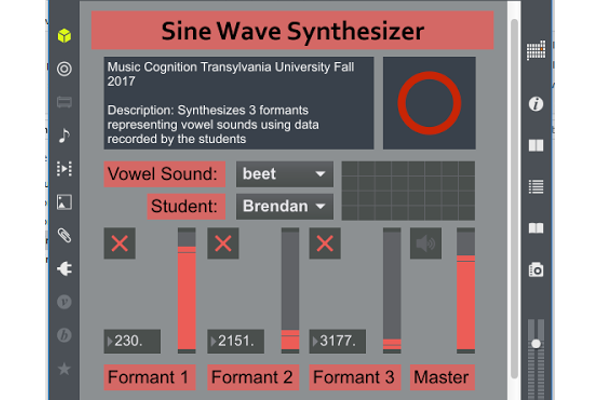

These Formant Analysis, Synthesis, and filtering tools were created for the Music Cognition course during the fall of 2017 at Transylvania University

Brendan Thompson

Tags: projects Audio

These Formant Analysis, Synthesis, and filtering tools were created for the Music Cognition course during the fall of 2017 at Transylvania University

Brendan Thompson

Tags: projects Audio

The Music Cognition class at Transylvania University take in interdisciplinary look at the way humans perceive music, which is a cross between Psychology and Music. These patches were created for the final research project. While others were pursuing more psychology based approaches with surveys and data, I took to developing tools that would aid future students and researchers in the field of Formant Analysis and Sine Wave Synthesis.

My goal for the final project was to develop software that could simplify the Sine Wave Synthesis process. I quickly saw that the simple way to do it would be to take the data we had already collected and generate tones at those pitches. I also realized that the hard way would be to take in audio and filter out everything except the formants. In the end, I ended up doing both. Throughout the process I conducted all sorts of research and invested hours into learning about the mathematics behind frequency analysis using the Fourier Transform. The complete project folder can be found in the GitHub Repository

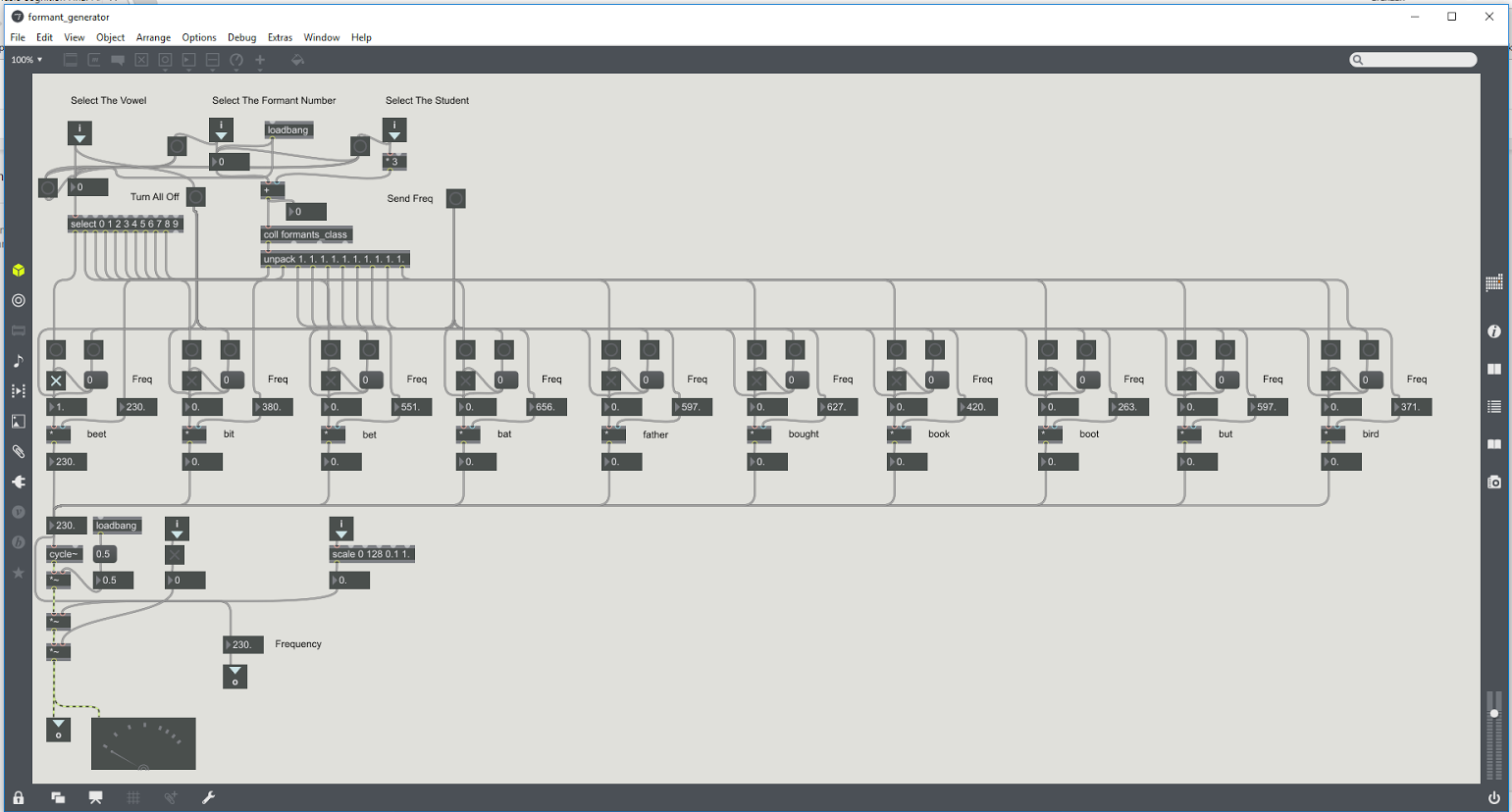

Building the Sine Wave Synthesizer was a rather straightforward process. Adding three synthesizers together was one of the first things I ever did in max. The only difficult part was to control the oscillators given a specific vowel selection and the data gathered on it. At the time, the only way I need to store data was using a “coll” object, which I had learned earlier in the semester for a project in the class Interactive Music and Multimedia. I quickly filled out the frequencies for each vowel sound given the spreadsheet filled out by the class.

The three different oscillators were all instances of the same object, a patch I created called a Formant_Generator. Each took in three parameters: the Vowel to Produce, the Formant Number, and the Student whose data to use. Within the generator, each vowel had its own cycle~ object, and was always passed the appropriate frequency. To implement this properly, whenever a parameter is changed, all of the frequencies are set. Then, using Max’s right to left order of operations, first every single oscillator is turned off and then the one representing the selected vowel is turned back on. The Formant_Generator then outputs that new signal to be played as well as the frequency to be displayed.

The actual Sine_Wave_Synthesizer was pretty simple. As mentioned before, it is basically just three instances of the Formant_Generator. The main patch manages the level for each generator, adds them all together, and multiplies the signal by an ADSR. I learned how to create an ADSR using the youtube video Introduction to MaxMSP: Envelopes by jamesrmooney. He goes over the line object using messages, and then shows how to control it using the function object’s graphical user interface. I learned about the panel object from another video, which I used along with a custom color scheme to make the patch easier to use and more visually appealing.

The Sine Wave Synthesizer did exactly what it wass supposed to do, but it didn’t make Sine Wave Synthesis any easier. In order for someone to add their own formants, it is a huge procces. The user would need to record their voice in different software, load it in pratt, run custom analysis software, manually analyse that data to record the formant frequencies, load it into the coll object, change the unpack object, and then add their name to the student selector. I believe it is a much better tool than trying to listen to it in Pro Tools, but it is still way to difficult.

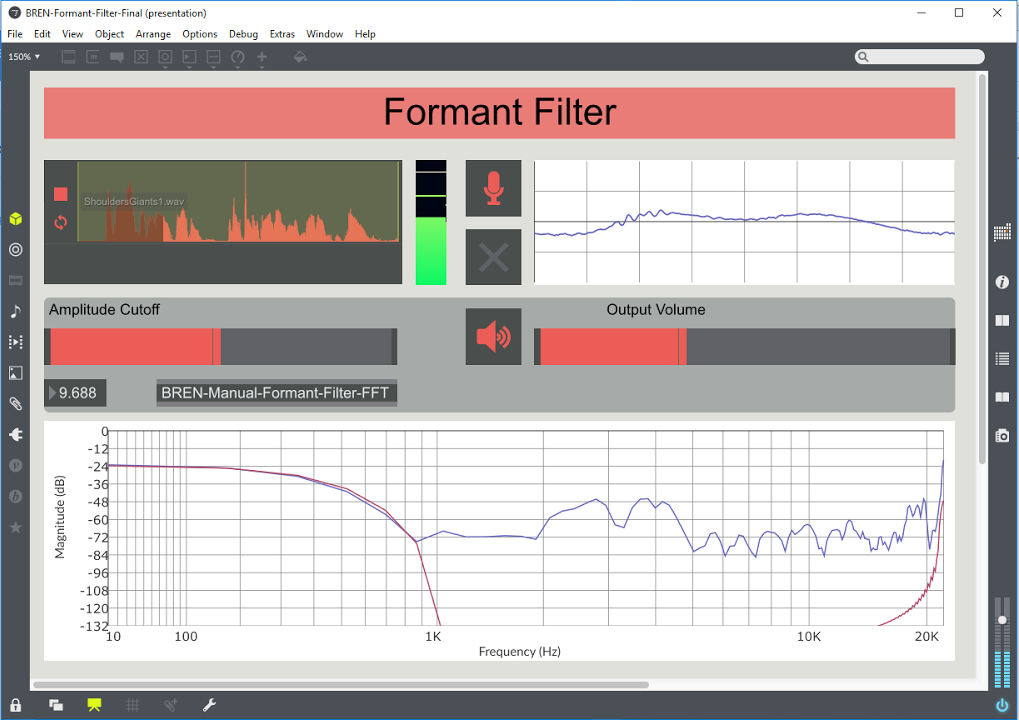

The Formant Filter was created because the Formant Synthesizer failed to simplify the Sine Wave Synthesis process as much as intended. The goal was to be able to take in an audio source, whether pre-recorded or spoken straight into a microphone, and output only the formants. I quickly realized that I would need to be analyzing the frequency spectrum of a complex wave, a task which when I started I had absolutely no idea how to accomplish.true. Otherwise, it continues executing at the next line.

My original research was quite disheartening. There were a few different forum posts where people had mentioned creating this very tool, but all of them ended empty handed. I quickly found myself bogged down with miscellaneous objects, third party externals, and useless help files. It became clear that I wasn’t going to get any direct help from the Max community.

My focus turned to the mathematical process of taking a wave from the time domain to the frequency domain. After studying a 10 minute introductory video on the Texas Instruments website and hearing about overlapping and windowing, I felt even more lost. I understood that the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was a mathematically quicker way to do a Discrete Fourier Transform, but I still didn’t understand the math or how to interpret the new output.

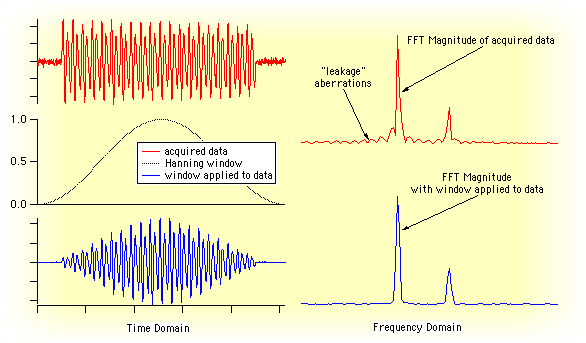

After slowly going through the video Using matlabs fft function 2 - zero padding and windowing by David Dorran I was finally starting to make sense of some of the concepts. He uses the matlab software to simulate all of the comlex mathematics and visual represent it in graphs. I realized that the FFT was an imperfect formula that introduced all sorts of errors in its output. The data that gets output by the formula shows the amplitude for each frequency band. However, there is only as many bands as the size of the buffer. For example, in a FFT given 512 samples, only 512 frequencies could be represented. The big issue is that it doesn’t mean that the spectrum is divided up equally and each band represents a specific range. Instead, only perfectly fitting frequencies properly display their amplitude. Any frequency that do not fit into a band result in terrible smearing and data that is far from correct. Another huge issue is that the FFT was only designed for discrete data sets. Therefore, when analyzing a continuous wave, the beginning and end of each chunk also gets messed up. These issues are where Windowing and Overlapping come in.

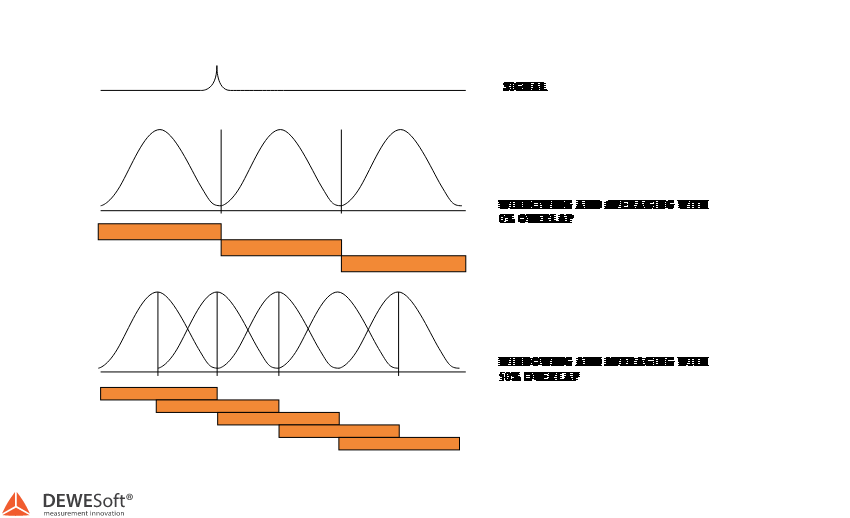

Windowing is the process of manipulating each chunk of samples so that the amplitudes at the beginning and the end are at zero. If the same window is applied after it is analyzed by the FFT, that data is significantly closer to what the original complex wave actually represented. There are multiple popular windows, most notable are the Hanning, Hamming, and the Blackman windows. Overlapping is the process of analyzing one chunk followed by the next chunk while simultaneously comparing the result to an overlapped analyzation of a chunk consisting of the end of the first half and the beginning of the next half. This process also works to remove some of the spectral leakage. The process of cleaning up the result of the FFT function is a complex and mathematically challenging concept.

Armed with significantly greater theory on the mathematics behind analyzing FFT output I was able to stumble across the holy grail of Max MSP Fourier Transforms: the tutorial series Advanced Max: FFTs Part 1 by Timothy Place. Not only had I stepped well passed my understanding of wave physics and signal processing, I had crossed over into the world of advanced Max programming. In the first video, which takes over 20 minutes to get through without stopping constantly to keep up, it goes over the pfft object, which is specifically designed for creating patches that build off the fft object. The first patch that it creates trims out all of the frequencies that are below a certain amplitude, and the second patch creates an EQ that allows for amplitude limiting of each frequency bin.

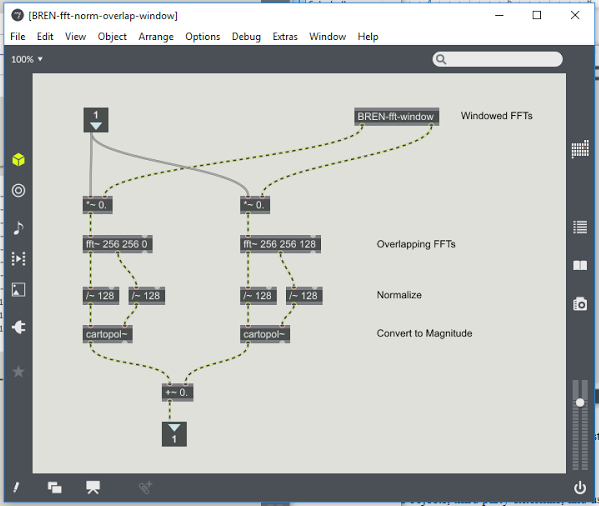

The pfft object was super helpful because it handles multiple advanced things by default, such as windowing and overlapping. However, in Part 2 of the series, the patches are stripped of the hand holding that is the pfft object and instead all of the processing is done explicitly. This includes creating the window, applying it to both sections of the overlapped ffts, and analyzing the data. These manually build FFTs where what ended up handling the final version of the Formant Filter.

The third video in the series was instrumental in helping me build the Filter. It is over 45 minutes long and I built my own patch alongside it on three separate occasions. This video took all of the math and the magic and showed me how to visually represent what was happening within Max. The final version of the filter includes these displays in a few different ways.

Part 4 of the series relied on Max For Live, which I didn’t have and therefore couldn’t follow along with. [Part 5](https://cycling74.com/tutorials/advanced-max-ffts-part-5) showed how to code patches in C. The video made the process look really straightforward, and gave me tons of hope toward successfully building the filter. However, after spending a good handful of hours struggling, I was never able to get a custom object to successfully run inside Max.

The process of building the Formant Filter was mind numbingly difficult. I spent hour after hour re-reading, re-watching, and re-doing tutorials in order to get a solid enough understanding to manipulate what I learned into what I needed it to be. In the end, the Filter was pretty much just a mix of the first three tutorial videos wrapped into a formant filter system. I was never able to properly analyze the spectrum to find the maximum amplitudes and reactively only let the loudest frequencies pass. The final version of the Filter allows for the user to either play a pre-recorded sound or to speak directly into the patch. They are presented with visual representations of the wave during each step of the way, and have to manually control the amplitude cutoff.

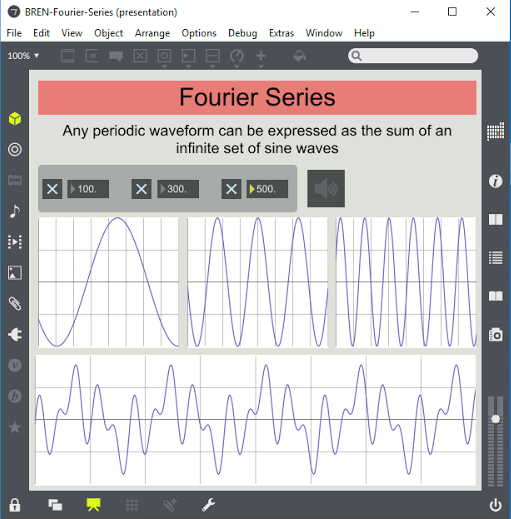

In order to present the patches and explain the technology behind the Fast Fourier Transform I developed two other patches. The Fourier Series patch shows basic additive synthesis using three different oscillators. It displays the three separate sine waves and shows what it looks like when they come together to create a complex waveform.

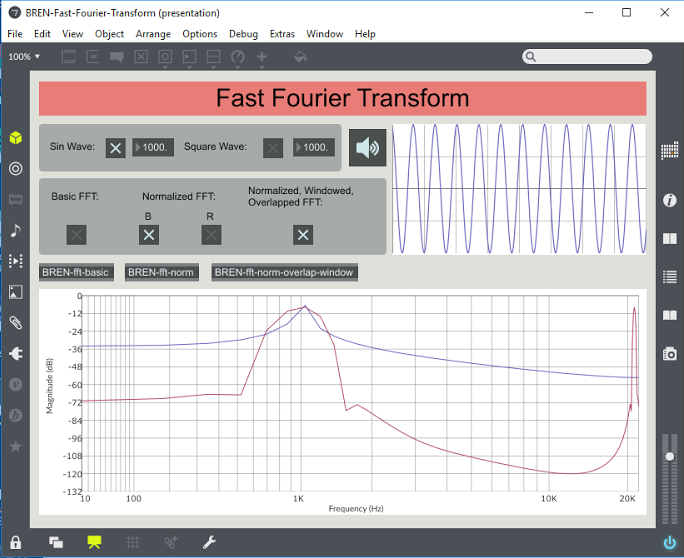

The second patch was created in an attempt to show the intensity behind the mathematics of the Fast Fourier Transform and give a taste of what needs to be done to the data in order to efficiently analyze it. The patch displays the waveform in the frequency domain at three different steps: what the FFT returns originally, the data normalized, and the data normalized, windowed, & overlapped.

The processes involved in creating these two formant analysis programs was significantly more difficult than I expected it to be. Although the Sin_Wave_Synthesizer cleanly represents vowel sounds, it is very far removed from taking in a voice and outputting the formants. The Formant Filter does a significantly better job at it, but it is still lacking in a few ways. Throughout the experience there were countless obstacles and so many points where my attempts seemed completely futile. However, after repeatedly hammering in the theory and going over the tutorials time and time again the concepts finally started coming together. My favorite quote of all time is “if I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” which was said by Isaac Newton. The only reason I was able to create that filter is because of the incredible work done by my predecessors: mathematicians, physicists, audio engineers, software developers, and other great minds within the Max community. The final version of the Formant Filter is very close to what I dreamed for it to be. With a little persistence and guidance it could really become a powerful open source tool not just for other Max enthusiasts but for all music lovers and especially music cognition specialists. Hopefully someday someone will climb up onto my shoulders and turn this tool into something great.